Recently, I learned about a lesser-known programming paradigm called "Choreographic Programming" that rather intrigued me.

When it comes to concurrent programming paradigms, my knowledge has largely been focused on the technical aspects of dealing with concurrency and the constructs one typically reaches for: mutexes, semaphores, condition variables, kernel threads, user-space aka "green" threads, coroutines, event loops. It wasn't until I learned about Choreographic Programming that I realized just how little I knew about actual paradigms for managing concurrent programs beyond your standard fare Actor Model or reactive programming.

Before we dive right into choreographies, we need to get a few things out of the way.

Session Type Formalism

In order to truly appreciate choreographies, we need to understand what a session type is. And by session here, I am not referring to the networking-associated, time-delimited, stateful session we typically think of.

Session in this context refers to a formal methodology and accompanying construct for specifying communication behavior in computer programs. First introduced in a conference paper submitted for the 1994 International Conference on Parallel Architectures and Languages Europe, session types offer a way to describe invariants around multi-party communication protocols. Even further, session types can actually be statically verified (hence the "type" in the name).

Let's consider the canonical example of an ATM. Here we have a typical client/server scenario with the following protocol:

- Client supplies an ID to the ATM

|

|---> If OK:

| |

| |---> Client requests DEPOSIT

| | |

| | |---> Client sends amount

| | |

| | |---> ATM responds with updated balance

| |

| |---> Client requests WITHDRAW

| |

| |---> Client sends amount to WITHDRAW

| |

| |---> ATM responds with:

| |

| |---> OK

| |

| |---> ERROR

|

|---> If ERROR:

|

|---> Session terminates

So how do we formalize this protocol such that we can describe it programmatically? Let's create a simple formalization:

ATM = recv ID; choose { OK: (ATMₐᵤₜₕ) | ERROR: (ε) }

ATMₐᵤₜₕ = offer { DEPOSIT: (recv u64; send u64; ε) | WITHDRAW: (recv u64; choose { OK: (ε), ERROR: (ε) })}Session types consist of four primary operations:

- send/recv, indicating sending and receiving messages of a particular type from the other party; and

- choose/offer, indicating a branching point at which the host party can choose to enter into one of several sub-protocols.

For the latter, our grammar describes such a sub-protocol where we either become authorized to use the ATM (ATMₐᵤₜₕ), or the ATM returns an ERROR.

Note, here we're describing communication behavior but not necessarily implementation. For example, in the first ERROR case we don't know the reasons for which a user's authentication might be rejected; we just know that it isn't. Also note, the semicolon in the grammar indicates a sequence of actions and the epsilon indicates the termination of the communication itself.

What we've done here is describe the protocol from the perspective of the server (the ATM). In session typing, we also describe the protocol from the point-of-view of the client. This — in session typing — is known as the dual. We need the dual so we can ultimately implement both and verify them against the session type. Let's throw together another formalization for the dual, in this case the client:

CLIENT = send ID; offer { OK: (CLIENTₐᵤₜₕ) | ERROR: (ε)}

CLIENTₐᵤₜₕ = choose { DEPOSIT: (send u64, recv u64; ε) | WITHDRAW: (send u64; offer { OK: (ε) | ERROR: (ε)})}You'll notice that CLIENT looks quite a bit like the ATM, but with the four operations reversed. And this is precisely the point! From this we can construct a dual session type, which ensures each party's protocol is consistent with the other's.

In practice, recursion is often used here, but I don't want to digress too much further than I already have. You can easily envision this if you consider whether ATM instead allowed the authenticated CLIENT to choose again instead of terminating.

So how does this look in practice? Suppose we had two channels — we would actually model these with types:

type AtmDeposit = Recv<u64, Send<u64, Close>>;

type AtmWithdraw = Recv<u64, Choose<Close, Close>>;

type AtmServer =

Recv<Id, Choose<Offer<AtmDeposit, AtmWithdraw>, Close>>;

type AtmClient = AtmServer::Dual;Where Dual here would allow us to swap, say, a recv for a send depending on whether we're referring to the ATM or the client.

Choreographies: The Basics

Okay, now we're adequately equipped with the requisite knowledge to understand Choreographic Programming. The idea of Choreographic Programming was solidified in computer scientist Fabrizio Montesi's titular 2013 PhD thesis. The choreography model existed prior to this thesis, but several issues severely limited its viability in practical application to distributed systems — namely that choreographies were typically prescribed to a single duality of client/server whereas distributed systems are multi-party, and that when applied to multi-party systems these original choreographies encounter a melange of race condition issues. The thesis is largely concerned with presenting proofs that demonstrate these limitations can be overcome. But for now, let's learn the short version.

Distributed Stuff is Hard

The thesis points out that the large majority of issues in concurrent distributed systems are focused around endpoint safety. Basically, it's challenging to ensure several nodes each abide by the constraints of the protocol in which they partake. This could be something as simple as many REST servers needing to communicate in a common payload format, or something as practical as several nodes participating in the internet using compliant HTTP.

Programming the communication flows between nodes is difficult, Montesi points out, because the prevailing programming paradigms focus on implementing systems discretely. That is, you don't write code for a client and a server at once; you go and implement a server, then you (or someone else) implement a client (or clients) that talk to it. The paper summarizes this, stating "expressing [communication flows] by defining the sending/receiving actions of each endpoint is difficult".

Endpoint Projection aka EPP

Choreographic programming alleviates this by allowing one to write the intended communication behavior of concurrent programs as a single logical unit. This is done by way of a procedure dubbed "Endpoint Projection", or EPP. Where a choreography is a single implementation of session types that describe a protocol, EPP is the process of compiling that choreography into multiple targets (for each participant).

Imagine writing the code to implement an auth protocol between a server and its clients, then compiling that code into separate modules that can then be used by the server and client applications. In EPP, a single program produces multiple modules for each role in the protocol described in that single program.

Thoughts

All of this has me thinking about the distributed systems we build at AWS. Obviously, AWS is a massive company with an even more massive ecosystem. I suppose an onlooker might think we've begun to figure out such issues as the aforementioned, but we really haven't. Because of the strict SLAs and high availability requirements, AWS systems easily wind up being comprised of many, many sub-systems and nodes therein.

The way we ensure such sub-systems follow protocol isn't any more special than the standard open source solutions out there right now. If you're interested in reading about one of the tools involved here, you can find the docs here. Now because I brought this up, I'm apparently obligated to state for the record that this blog comprises my thoughts and opinions; in no way whatsoever are they representative of my employer. Not that this is particularly ambiguous.

There's a lot more interesting stuff in the thesis, and I'd recommend checking out at least one of the few Choreographic libraries out there such as Choral. A lot of these are oriented towards the emergent class of specialty langs designed for distributed programming. Now that it's top-of-mind, I've been meaning to check out Unison, which sounds quite interesting. Next time!

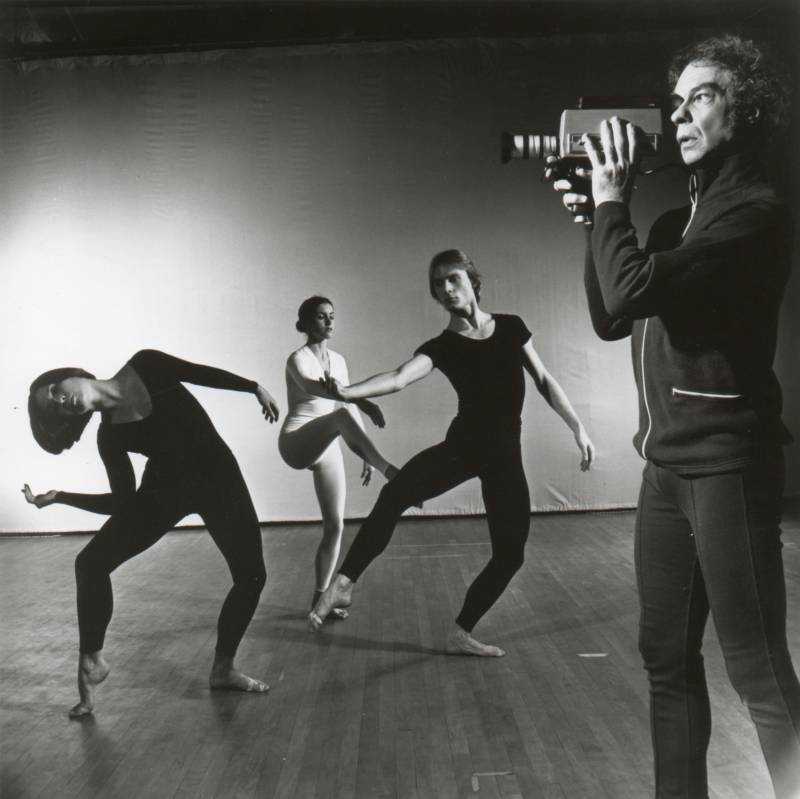

This post's photograph is a picture of assorted people, among them Merce Cunningham — my favorite choreographer. I'll update this with a link once I post something about dance choreography.